As part of an ongoing programme of creative engagement with the Borough Road Collection, this piece brings curator Theresa and composer Tom Sochas into conversation around David Bomberg’s Self-Portrait.. A Franco-American pianist and composer born and raised between Paris and Nairobi, Sochas has developed a distinctive musical language shaped by jazz, lyrical melody, and Western classical traditions. Now based in London, his practice spans performance, composition, and cross-disciplinary collaboration. In this dialogue, Sochas discusses how historical context, materiality, and artistic identity informed his compositional approach, and how working closely with an archive collection opened up new ways of thinking about sound, memory, and interpretation.

David Bomberg’s Self-Portrait occupies a significant position within the Borough Road Collection, both as a statement of artistic intent and as a work shaped by the social and historical pressures of its time. When you first encountered the painting in the collection, what aspects of it stood out to you most strongly?

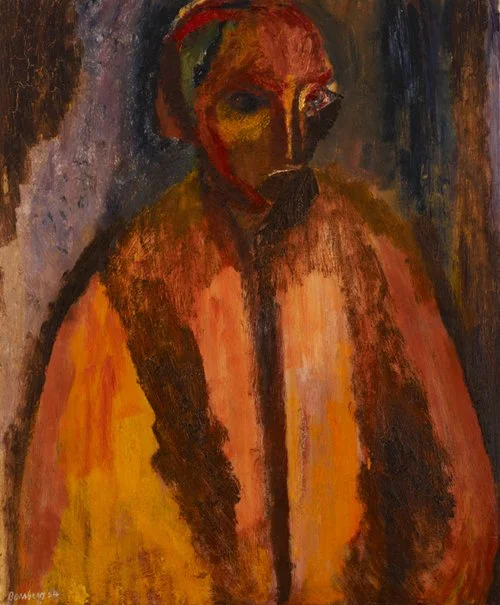

What first struck me in the piece was an apparent dialogue between this spectral, almost haunted character, with burnt colours juxtaposed onto this childlike figure. The viewpoint coming from above accentuating the innocence and vulnerability.

Bomberg’s biography , particularly his experience of both World Wars , is often central to curatorial interpretations of his work, as is the pedagogical legacy of the Borough Group. How did this historical context inform your musical response?

David Bomberg having lived and worked through both world wars certainly influenced my thoughts when it came to both the music and my interpretation of the painting. What it suggests to me is an artist trying to navigate sheltering his child-like innocence, curiosity and openness to the world in order to create art in a world filled with violence, trauma and tragedy.

From a curatorial perspective, Self-Portrait is notable for its material presence and almost sculptural handling of paint. Did you find yourself responding to Bomberg’s painterly language through musical decisions?

The woody textures that cut through the painting were very inviting and inspiring when it came to thinking about instrumentation, which is why I chose to go for a duet between two wooden instruments, the piano, and the queen of wood instruments : the violin.

Responding to collection works through sound introduces a different temporal and sensory dimension to interpretation. Could you describe your compositional process for this piece?

My creative process is usually pretty instantaneous. I knew when I saw the painting that music would likely invite itself in easily. I wanted to create something that could blend this sense of tragedy and dread with hope and innocence. The long repeated sustained piano chords would move the harmony forwards in a stately but subdued fashion and the violin would have plenty of breathing room. First the I wrote the piano, trying to find the right chord progression to express an intricate and delicate balance between the dark and the light. In hindsight you can certainly hear some Messiaen in there which is rather fitting as he wrote much of his best work in the confines of a concentration camp, he is perhaps the master of hope. Once I had a rough sketch I started painting in the violin, this took a while and had many back and forths. In the end the melody informed the harmony and I had to go back and make changes to the harmony in order to support the melody that was drawing itself out. I couldn’t be luckier to have the great Elena Jauregui record the violin part. She is a one of a kind musician and violinist.

Improvisation is central to your wider practice. How does that way of working intersect with a composed response to an archival artwork?

As an improviser, the chief goal is to abandon any goal and be absolutely present and listening to the moment and what wants or needs to be expressed in that moment. I think being practiced at improvisation always informs the composition process, especially in the early stages when you have to listen hard enough to the note or chord you’ve just written in a way that it may show you what must come next. It also gives you a certain playfulness that allows you to consider other musical options or to allow yourself to make mistakes, some of which may very well be the best thing you end up writing.

Bomberg’s Self-Portrait can be understood as a reflection on artistic identity shaped by historical upheaval. Did that theme resonate with your own position as a contemporary composer?

I think the perceived theme of that self-portrait felt particularly interesting to me as an artist as, though I am privileged enough not to be stuck in a war-zone, I am very much aware of the absolute madness that is currently taking place in our world. Be it the rise of the far right, the threat of a global conflict, or the Palestinian genocide (to name only a fraction of the tragic events taking place as we speak).

From an institutional standpoint, projects such as this open up new ways of activating archive collections. How did working directly with the Borough Road Collection differ from other commissions you’ve undertaken?

This experience was so enriching, spending time with the work up close, carefully unboxing it and getting some fascinating insight into the work from the curator themselves was super special and exciting.

When this work is encountered by audiences alongside Bomberg’s Self-Portrait, what do you hope it adds to their experience of the painting?

I hope they get through the piece without stopping half-way haha!

Looking ahead do you see this project as a starting point for further engagement with the Borough Road Collection or for future cross-disciplinary collaborations?

I would love to compose again for a piece in the collection, I’m not sure which I’d choose but I’d certainly love to experience discovering them again at the archive and sitting with more of the work in a quiet room.

You can hear Tom’s piece below